Charles Brennan provided testimony in support of House Bill 24-1129, Protections for Delivery Network Company Drivers. CCLP is in support of HB24-1129.

Recent articles

CCLP testifies in support of TANF grant rule change

CCLP's Emeritus Advisor, Chaer Robert, provided written testimony in support of the CDHS rule on the COLA increase for TANF recipients. If the rule is adopted, the cost of living increase would go into effect on July 1, 2024.

CCLP testifies in support of updating protections for mobile home park residents

Charles Brennan provided testimony in support of House Bill 24-1294, Mobile Homes in Mobile Home Parks. CCLP is in support of HB24-1294.

CCLP’s legislative watch for April 5, 2024

For the 2024 legislative session, CCLP is keeping its eye on bills focused on expanding access to justice, removing administrative burden, preserving affordable communities, advocating for progressive tax and wage policies, and reducing health care costs.

Working Colorado: Is college-level earning power flattening?

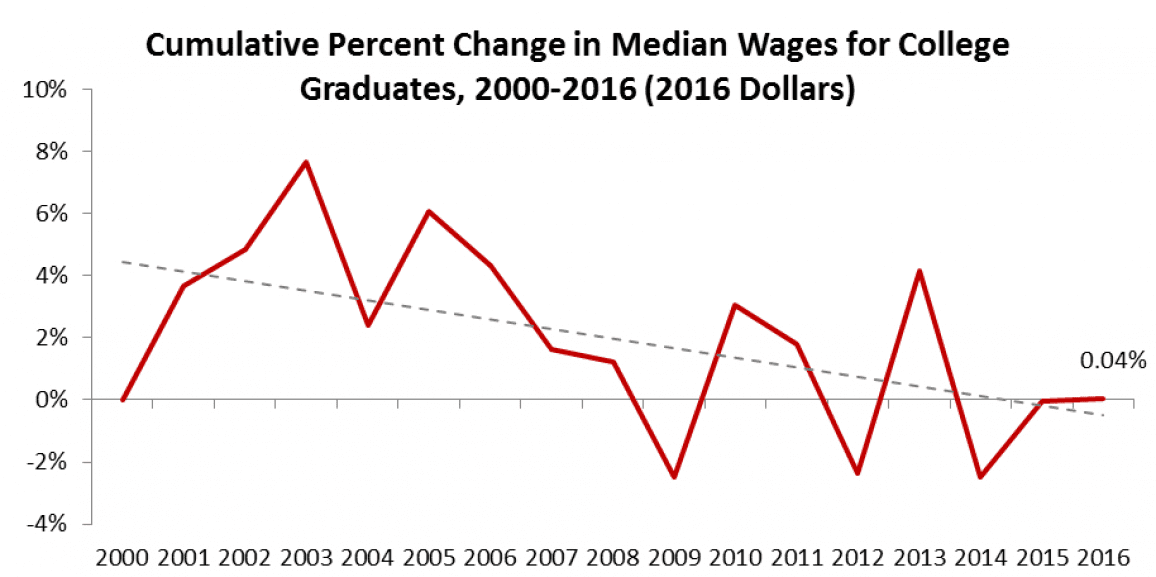

The conventional wisdom that college grads earn more than those with less education still holds true today. According to 2016 data, annual median earnings for college graduates were nearly $24,000 greater than for Coloradans who stopped at high school. What’s changed, however, is that wages for college graduates have essentially stalled. College-educated workers in Colorado haven’t seen a meaningful raise in years. The 2016 median wage of college graduates was essentially the same as it was in 2000.

College graduates experienced a short-lived period of rising wages during the technology boom of the late 1990s which slowed as the U.S. economy approached the Great Recession. Since then, college graduate wages have remained mostly stagnant. For certain, college graduates are doing better than high school graduates whose wages are down 8.1 percent in Colorado since 2000. Essentially, college graduates have been treading water while workers with less education have fallen farther behind. Here are a few possible explanations for this wage stagnation for college graduates:

Median Earnings in Colorado, by Education, 2016

| Median Annual Earnings | |

| Less than High School | $25,900 |

| High School or less | $31,700 |

| Some College | $35,900 |

| Bachelor’s or more | $55,600 |

Shifting job market – – One factor is that the economy has failed to produce enough jobs for college-educated workers. In the early years of the post-recession recovery, high-skill (engineering, management and technology) and lower-skill jobs (maintenance, food service and sales) returned first. The middle-skill jobs were slower to return, in part because this broad category includes some industries hardest hit by the recession such as construction. Many middle-skill jobs were also replaced by technology. Fortunately, middle-skill jobs have recovered in recent years, according to a new analysis by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. This broad middle skill category has mostly seen growth in jobs requiring some post-secondary education or training, such as health-care technicians and paralegals.

College graduates settling for lower-skilled and lower-wage jobs – – With fewer jobs that require a college education, more college-educated workers are taking lower-skilled and lower-paying jobs. Lower demand for advanced degree holders leads more highly qualified workers — those with advanced and graduate degrees — to compete for slightly lesser-skilled work. In 2015, 44.6 percent of young college graduates were working in jobs that did not require a college degree — up from 38 percent in 2000. Furthermore, the quality of these jobs changed. According to the Economic Policy Institute, these “non-college” jobs occupied today by college-educated workers offer less career advancement and are lower-paying. In 2000, about 55 percent of college educated workers in “non-college” jobs earned at least $45,000 a year. In 2015, only 44 percent of these workers were in jobs that earned that much.

Yet, college is becoming “a must” to compete in the job market – – All this is occurring at a time when college graduates are becoming a larger part of the labor force. According to a 2016 report by Georgetown’s Center on Education and Workforce, nationally, those with a bachelor’s degree or higher make up 36 percent of the labor force. This is the first time college-educated workers slightly outnumber high-school educated workers in the United States. But this means tougher job competition for workers at the lower end of the pay spectrum. Since the recession ended, the vast majority of the jobs created have gone to workers with at least some college education. Employers are now requiring more education from applicants for jobs that previously required less education.

The majority of Colorado workers are experiencing wage stagnation. Unfortunately, in today’s economy, a college degree does not necessarily provide immunity to the trend of stalled wages. The result is that while a college education is a prerequisite for moving into the middle class, it no longer guarantees the opportunity for financial gains over time.

Wage growth for our state’s educated workers is essential to growing our economy and requires action that would benefit all workers. Pay and productivity used to rise in tandem. Yet, with eroding labor and wage protections that is no longer the case and the result is wage stagnation for most workers in the state, even our college educated workers.

Robust public policy that ensures economic growth is broadly shared is the solution. That includes strengthening labor standards and collective bargaining rights, updating sick and paid family leave, and ending discriminatory practices that contribute to race and gender inequities.

– Jesus Loayza